The Cape Town Grain Elevator was opened in August 1924, closed in August 2001, and stood derelict and neglected for the next decade.

My own interest in the site began in 1994, and it subsequently became a major element of my PhD thesis “Gas and Grain: The Conservation of Networked Industrial Landscapes” (University of Cape Town, 2004).

Since 2012, London based architect Thomas Heatherwick, has been transforming the elevator for reuse. The upper levels of the elevator house are now The Silo Hotel (opened March 2017). The remainder of the elevator house, together with the storage annexe, opened as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, on 24th September 2017.

What is a Grain Elevator?

A Grain Elevator has two primary functions: (a) mechanical handling of grain in bulk, and (b) safe storage of grain in suitable bins (silos). Grain is deposited in bulk into the ‘boot’ of a vertical elevator ‘leg’, which consists of a continuous belt running over two pulleys. At regular intervals along the belt metal buckets are attached and, as the pulleys revolve, these buckets scoop up grain from the ‘boot’ and carry it to the head of the elevator, where the grain is turned out by the inversion of the buckets into a spout through which the grain is fed on to a conveyor belt and delivered into storage bins or silos.

When discharging the grain from the elevator, it is drawn from the bottom of the bins, lifted as before, and delivered on to a belt conveyor, to be discharged by gravity, through spouts, into ships or railway trucks.

Before the introduction of elevators, all grain handling was carried out in 200lb bags, and the change to bulk handling meant that an entire system of elevators had to be introduced simultaneously for it to be effective. To this end, thirty-four ‘country elevators’ were built at stations handling large volumes of grain traffic. Only one, at Moorreesburg, served the wheatlands of the Western Cape, whilst the remainder were all located in the maize producing areas of what were then known as the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. In addition, two port, or ‘terminal’ elevators were built, at Cape Town and Durban.

The total storage capacity of the new system was 181,200 tons, of which the elevators at Cape Town and Durban accounted for 30,000 and 42,000 tons respectively. The functions of the system, which was from the outset controlled by South African Railways and Harbours, included grading, weighing, cleaning, storing and handling of grain

Cape Town’s Grain Elevator can’t therefore be seen in isolation, but has to be regarded as an integral part of a system that covered the entire country. Alone, it would have had no use, and indeed, would never have been built.

The building of the Cape Town Grain Elevator

Cape Town, lying one thousand miles from the major grain producing areas, was always a marginal choice for the location of the second port elevator, which it nearly lost to the competing claims of East London. However, the increased railage cost was offset by the four day advantage in sailing time to Europe. Cape Town was also seen as being better placed to serve the wheat producing areas of the Western Cape, which would not compete with the needs of the maize growers due to their different harvesting cycles.

Lack of available space at Table Bay Harbour led to early suggestions of the quarry site being used for the elevator, but as this would have been too expensive, the site on the Knuckle on the South Arm was selected as the only practicable alternative.

Canadian A W Menkins, based in Durban, was appointed by South African Railways and Harbours as principal contractor, for the construction of all the elevators, with Mr Littlejohn Phillip, as Consulting Engineer. Work on the foundations of Cape Town’s elevator began in 1921, though with some initial difficulties which caused the railway authority to bring Mr Edmund Xavier Brain in as Resident Engineer. By February 1923, the problems had been overcome, and work on the superstructure was commenced in June that year.

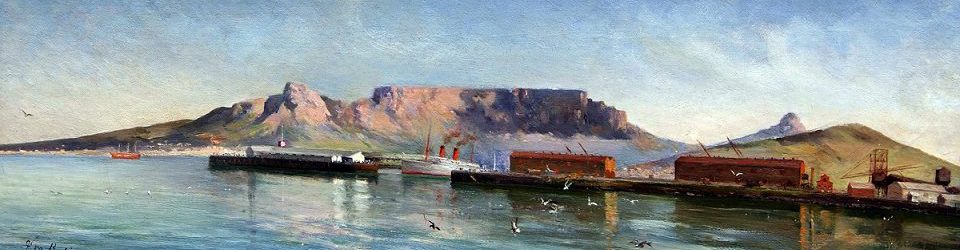

Work continued on the “grey towering slab of concrete” throughout the day and night, with up to 1,000 men being employed on the construction at any one time. Apart from claiming the record as South Africa’s highest building, at 180 feet (57 metres), the elevator also claimed a world record for having had 4,800 cubic yards of concreting done in 14.5 days. Statistics made available to the Cape Argus of 17th May 1924 recorded the use of 17,500 bags of Cape Portland cement and 145 tons of reinforcing steel in the storage bins. The reporter, viewing Cape Town from the harbour suggested that “a stranger might very well be excused for forming the impression that the Mother City of South Africa was nothing but a smoke belching congestion of factories”.

The early use of the Grain Elevator

In August 1924, a party including the Ministers of Railways, of Mines and Industries, and of Agriculture, together with the General Manager of South African Railways and Harbours, were witness to a successful trial run of the Cape Town elevator. In the same month, thirty-three country elevators were opened in the maize areas.

The first load of maize was received into the Grain Elevator at Cape Town on 8th September 1924, and this was followed two months later by the first export from the new elevator, of 6,245 tons of maize aboard the ‘S S Willaston’, on 12th November 1924.

While the elevator was reported as having a shipping capacity of 750 tons per hour, this was rarely achieved at first due to time lost trimming vessels, many of which were not equipped for elevator operation. The system was judged a success, however, and many requests were made for the construction of additional country elevators.

The recent history of the Grain Elevator

South Africa now has three port, or ‘terminal’ elevators, with the most recent being opened at East London in 1966. The elevators at Durban and East London continue to be operated by Portnet. Like that at Cape Town, they are bucket type elevators.

Cape Town’s Grain Elevator complex, excluding the conveyor gallery and the ship loaders,was leased by Portnet (and then the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront Company) to W P (Koöp) BPK from 1987 to 2001. WPK is a farmer’s co-operative, and acted as a wholesaler, warehouser and distributor. WPK bought grain, and sold it to whoever wanted it, whether member farmers or anyone else. Among the grains handled by the elevator were Wheat, Yellow Maize, White Maize, Grain Sorghum, Tapioca, Soya, Oats, Sunflower Oil Cake, Cotton Oil Cake and Malt.

The increased length and draught of modern bulk grain carriers meant that many were unable to berth at the Collier Jetty, and the high rail costs from the maize producing areas, have resulted in the virtual cessation of grain exports from Cape Town.

The last export shipment from the elevator, comprising 21,450 metric tons of barley, was loaded in July 1995, on to the M.V Anangel Wisdom. It is now unclear what the future of the overhead conveyor gallery and the associated loaders will be.

The components and functions of Cape Town’s Grain Elevator complex

The working house of the Cape Town elevator has a steel frame, but the storage bins (‘silos’) are of slip-formed reinforced concrete. Although early grain bins were built of wrought iron or steel, these materials had the disadvantages of high costs, a need for specialised construction skills, a tendency to rust and corrosion, and poor thermal insulation properties. Ferro-concrete, which was soon to became the standard building material for grain elevators throughout the world, was also recommended as the most suitable material for use next to the sea.

The principal components of the Grain Elevator site

Four lines of railway track served the track shed, where all grain taken into the Grain Elevator was first received. Each of the railway tracks served a single below ground hopper, into which grain was discharged from railway trucks. Two types of truck were used, the first of which was flat bottomed, and needed to be tipped end on to discharge its cargo. The second type, which had hopper shaped sections in its floor, was simply discharged by opening valves in the bottom of the truck.

Each of the intake hopper positions in the track shed was served by a hydraulic lift, by means of which railway trucks could be lifted to an angle of approximately 45 degrees in order to discharge their cargo through gates in the end of each truck.

The Working House

The 57 metre tall, tower like structure, known as the working house, served a multitude of functions. It received grain from the track shed; lifted it to the top of the building by the use of elevators; and provided facilities for it to be weighed, cleaned, bagged, stored and distributed. Rectangular grain bins in the working house are constructed of reinforced concrete, with steel bases. The bins are built on circular concrete pillars extending into the basement, and then on piles driven into the ground below that.

Two principal types of machine were used for moving grain, the elevator, for vertical movement, and the conveyor, for horizontal movement. All machinery was supplied by Henry Simon Ltd, of Manchester, England, and remained largely as it was when it was installed. There were a total of seven elevators in the working house, three intake elevators on the west side, and three shipping elevators on the east side. A spare elevator was also situated on the west side. Each elevator consisted of a chain-driven endless rubber belt, to which was attached a series of steel buckets. As the full buckets reached the top of the elevator, they were inverted, spilling the grain into chutes which directed it to the next level.

Series of man elevators and fireman’s poles were provided inside the working house, (though only at the level of the top five floors). Each man elevator consisted of an endless rubber belt, running vertically, which had handles and small ledges attached at regular intervals, allowing a man to step on to it and ride up or down one floor at a time as required. The fireman’s poles allowed rapid descent from each floor to the next.

The top floor of the elevator, known as the machine floor, allowed access to the heads of the elevators, and contained all the electric motors and chain drive mechanisms which powered the elevators.

Moving down thorough the working house, the first level below the top was the ‘Upper Scale Floor’. On the intake (west) side of the building, there were three 48 ton pre-weighing scales, known as ‘garners’ or ‘dormant scales’, each serving a single intake elevator. On the shipping (east) side of the working house there were three automatic scales of 6 tons capacity, serving the shipping elevators. A fourth automatic scale was located on the west side as a spare.

On the Lower Scale Floor, the actual scales were positioned immediately below each of the pre-weighers, and each pair could really be considered as part of a single machine.

Below the scales was a floor containing nothing more than an arrangement of flexible spouts, the articulation of which allowed grain to be directed as required to the required place on the next level.

On the Distribution Floor there were two horizontal belt conveyors running on the north-south axis through the building. These ‘crossbelts’ were raised on a mezzanine structure, and were the only reversible belts in the whole complex. Each was provided with a movable ‘feeder’, which collected the grain directed into it from the Spout Floor above, and a movable ‘tripper’. The ‘tripper’ took the grain from the moving belt, and delivered it to the spout below. Both ‘feeders’ and ‘trippers’ were chain driven. Grain taken from these conveyors was then passed either directly into the working bins, or onto another set of conveyors, running on the east-west axis, to be taken to the storage annexe.

There were a total of 44 rectangular storage bins in the working house at what would normally be considered as ‘first floor level’.

On the ground floor, underneath the working bins, was the Work Floor. Here there were various machines, such as a Cleaning Machine, a Bag Sewer and a Bag Lifter. Along the eastern side of the building, a conveyor running from south to north took grain to the north east corner, where it was in turn loaded onto another set of belts serving the conveyor gallery.

The shipping side of the Basement was fitted with a steel mezzanine floor, onto which led six tunnels (two per elevator) running from the six lines of bins in the storage annexe. Horizontal conveyors moved the grain from the bottom of the bins to chutes, which in turn led to the boots of the shipping elevators.

At the lowest point of the working house, in the basement of the working house, were the ‘boots’ of the bucket elevators. On the intake side of the building, there were tunnels leading from each of the receiving hoppers in the track shed.

The Storage Annexe

The storage annexe was separated from the working house. However, it was connected by bridges to the scale floors of the working house, and tunnels to the basement of the working house.

Above the bins, in the ‘headworks’, were three identical horizontal conveyor systems, running at right angles to the east wall of the working house. Each system used endless rubber belts to carry grain from the working house and deposit it, by means of a ‘tripper’ and a chute, into the required storage bin.

The larger, circular grain bins in the storage annexe, set in seven rows of six, lay parallel to the east wall of the working house. The grain bins were constructed of massed reinforced concrete, and each was capable of containing approximately 500 tons of grain. Set in the spaces between the larger bins were thirty smaller ‘star’ bins, each capable of containing approximately 120 tons of grain.

Six below ground tunnels allowed for the transfer of grain back to the working house from the storage annexe. Grain was dropped from the base of the silo into a ‘feeder’ which directed it onto a continuous rubber belt, from where it was carried into the basement of the working house.

The aluminium clad steel structure on top of the storage annexe was used as an office and look-out station by the Port Captain from about 1935, until it was rendered redundant by the Lourens Muller Building. More recently it was used by to house telecommunications equipment.

The Conveyor Gallery to the ‘Collier Jetty’

The raised conveyor gallery, was constructed of steel members, and was clad corrugated iron sheeting. Four horizontal conveyors, with trippers, ran the length of the gallery, with two on each side of the gallery, one above the other. At regular intervals along the gallery, chutes in the floor were designed to receive grain taken off the belts by the tripper, which then dropped into the boot of one of the ship loaders.

The Ship Loaders

Until 1995 all four of the original ship loaders stood on the south side of the Collier Jetty. However, two were then broken up and sold for scrap, and the remaining two were relocated to the north side of the jetty. Each loader moved along rails laid on the collier jetty, using electricity supplied, to the chute nearest to where it was needed. It could then receive grain into its own internal elevator, which was simply a smaller version of those to be found in the working house. The telescopic spouts from the top of the loaders, were directed into the holds of the ship being loaded.

The Hydraulic Accumulator House

The hydraulic power for the truck lifts was produced on site by the application of electrical power to pump water to a pair of hydraulic accumulators. Each of the two accumulator ‘tables’ was supported on three steel pylons and was filled with concrete, scrap railway line and similar steel. The accumulators each had a simple trip mechanism which shut off the pump when they had reached full height, or re-activated it when they had dropped to half height.

The importance of the Grain Elevator as a part of Cape Town’s industrial heritage

The Grain Elevator complex forms a unique industrial site, within the broader landscape of Table Bay Harbour. Its early importance, as an export facility, was largely in terms of international trade, and the facilities it afforded to the national and regional agricultural economies. To Cape Town, its significance is that of a major contributor to the economic activities related to Table Bay Harbour. In more recent times, its importance has been of a regional nature, principally serving the Western Cape farming community.

The principal component structures within the site are indivisibly linked in their purpose, and should not generally be regarded separately, thus without the elevator and conveyor machinery, the value of the site would be much diminished, though not wholly lost.

The building of Cape Town’s Grain Elevator is well documented, and we are fortunate to have not only contemporary reports and original drawings, but also photographs taken during the construction stage. Thus there is potential for extensive research into this site.

The principal structures remained in use for almost 80 years, and when the site closed, were still in good working order, and apparently structurally sound. The exception was the conveyor gallery, which had deteriorated badly after the corrugated iron cladding was removed.

The hydraulic accumulators, the elevators, conveyors and scales all continued to serve the purpose for which they were constructed. It was only the conveyor gallery and the ship loaders that were not in regular use, although it had been demonstrated that they could still be operated if required.

The Grain Elevator is thus an important asset in the industrial heritage of Cape Town, and an appropriate conservation management policy for the principal components of the site should be formulated.

Public access to the Grain Elevator is necessarily limited by its very nature. It was a dusty working environment, with moving machinery, railway traffic and other potential dangers. It is part of the ‘Docks’, not the ‘Waterfront’. However, apart from the wonderful views that the upper floors afford of Cape Town, the Harbour and the Waterfront, the Grain Elevator was also a place of exciting activity, potentially allowing the visitor to witness such impressive sights such as hydraulic machinery lifting 45 ton railway wagons. Ways to safely allow the public to see some of this activity, which would have not only educational potential, but would no doubt be a significant tourist draw as well.

It is a very positive development that the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront Company, the owners of the site, now recognise the importance of all the components of the site, and are taking steps to ensure that it is realistically conserved and re-used. Apart from the aspects of cultural significance outlined above, it is also a significant factor in the ‘working harbour’ which the Waterfront originally claimed it wished to integrate with the modern development.

[Original text copyright David Worth, 1995, amended June 2013 and March 2014.]

South Africa’s Country Grain Elevators

Thirty-three of the original thirty-four country elevators survive. Some are derelict, while others have been heavily modified and incorporated into modern grain handling facilities. The port elevator at Durban harbour is also still in use.

for further information please contact davidworth@icloud.com