“A Smoke Belching Congestion of Factories”:

Cape Town’s Neglected Industrial Heritage (1998)

The following paper was presented at the Second Latin American Conference on Recovery and Conservation of Industrial Heritage, held in Cuba, from 8th to 10th September 1998.

General Introduction

Introduction to Cape Town and South Africa

Cape Town’s Industries

A Neglected Heritage

Case Studies

Strategies for the Future

Summary

General Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine the depressed state of Industrial Archaeology as a discipline in South Africa, and to consider how this impacts on conservation of the industrial heritage in the city of Cape Town.

After some introductory comments about industrialisation in South Africa generally, and more specifically Cape Town, the paper argues why South Africa’s industrial heritage may be said to have been neglected.

This ‘neglect’ will be demonstrated with reference to a number of case studies, including the Woodstock Gas Works, and the Grain Elevator in Cape Town Docks.

Finally the paper suggests strategies for the future. How do we redress past neglect for one relatively narrow field of interest, in a country where the heritage of the majority of the population has until now been seriously neglected?

Introduction to South Africa and Cape Town

Popular histories record Cape Town’s story as starting in 1652, with the establishment of a provisioning station by the Dutch East India Company. Control of the region was subsequently transferred from Holland to Great Britain at the beginning of the nineteenth century. South Africa became an independent republic in 1961, and, after many difficult years, gained full democracy in 1994 with the election of the ANC government led by Nelson Mandela.

Recent revisionist histories, by writers such as Nigel Worden and Vivian Bickford-Smith, have shown how firmly racial policies, that were to evolve into “apartheid” by the middle of the twentieth century, were already entrenched in the British governed colony of the nineteenth century.

Today, Cape Town promotes itself as South Africa’s “Mother City”, and promises visitors beautiful beaches and mountains, clear blue skies, a wealth of history, and access to game parks with elephant, rhino and lion.

To a certain extent that’s all true, and Cape Town is not the first place anyone would think about looking for an industrial history, or indeed for industrial archaeology.

Yet in 1924, a journalist writing for the Cape Argus, said that “a stranger might very well be excused for forming the impression that the Mother City of South Africa was nothing but a smoke belching congestion of factories”.

At the University of Cape Town, The Research Unit for the Archaeology of Cape Town is examining industrial sites in the context of a broader assessment of nineteenth century material culture.

Cape Town’s Industries

Cape Town is usually thought of as a commercial, rather than an industrial, centre. The more significant industrial concerns in the country are located far away, and it is there we find the extractive industries, predominantly gold and coal, that have underpinned the country’s industrial and economic growth.

With the abolition of slavery in 1834, and the subsequent emancipation in 1838 of slaves held in the Cape Colony, slave owners were compensated in cash for their “losses”. The resulting influx of capital into Cape society was largely invested in commerce, industry or property from which rents could be obtained.

In the earlier part of the nineteenth century, industrial activity in Cape Town was similar to what might be expected in any small market town of the same period. Brewers, tinsmiths, coopers, tanners, bakers, joiners and soap manufacturers are all represented in the Almanac of 1834.

However, by as late as the 1870s Cape Town’s economy was still dominated by a handful of merchants, and local industry was limited to satisfying immediate local needs. With no local source of cheap fuel, there were few factories, with little capital investment.

The discoveries of diamonds, in Kimberley, and gold, on the Witwatersrand, transformed the economy of South Africa during the latter part of the nineteenth century, and it is these industries that continue to underpin the country’s economy. As new industrial centres, including the city of Johannesburg, were created out of nothing, the domestic market for Cape Town’s commercial and industrial interests grew, while it continued to be the major port for the Cape Colony’s imports and exports.

A Neglected Heritage

This paper argues that South Africa’s industrial heritage has been neglected by the public; by professionals and academics; and by commercial and political interests.

However, in claiming that our industrial heritage is important, we have to recognise that the complaints about neglect of that heritage are magnified many times by the complaints of those who say that South Africa’s heritage generally does not reflect their cultural values, their heritage or their aspirations. As with so much in South Africa, it is the cultural values of European and other settlers, that have until recently predominated: that is, those of the colonists, not the colonised.

The particular relevance of industrial history, is that all racial, economic, religious, political and social groups are represented at the workplace. Industrial history is indivisibly linked to that of the people, however advantaged or disadvantaged by that history they may have been.

It is also suggested that the industrial heritage of countries in the developing world, such as South Africa, contains rare survivals that are no longer found in the nations of the developed world.

In South Africa there is no public awareness that industrial sites can have “cultural significance”, or “heritage value”. When one speaks of “heritage” in South Africa, one is generally talking about a Euro-centric notion of heritage which commemorates great men and events, and pretty buildings.

History is sanitised, and visitors to great wine estates, such as Groot Constantia, are shown the undoubtedly grand house symbolising the power and authority of the land owner; with no mention being made of the many slaves who laboured there. South Africa’s selection of National Monuments is built on the tradition of recognising great houses such as these, with their distinctive “Cape Dutch” gables. And from this tradition has grown the fashion of having “conservation studies” carried out by practising architects, who then largely use architectural and other aesthetic criteria for establishing what is worthy of conservation.

Professor Martin Hall wrote in 1989 that, “relatively little attention would be given to a snuff and tobacco factory in Cape Town, because Industrial Archaeology of the late nineteenth century is not a research focus” confirming Industrial Archaeology’s place in the twilight zone of archaeology.

To date there has been no formal survey of Industrial Archaeology in South Africa. There have been a number of Conservation Studies written about industrial sites, usually by architects, but these have invariably been ad hoc responses to development and other economic initiatives, as happens everywhere. Whilst there has been some interest shown in specific industrial sites, this has principally been due to the personal interests of individuals, with mixed results.

Cape Town’s leading conservation architects and architectural historians have all carried out Conservation Studies in recent years. Unsurprisingly, in all cases the emphasis has been on aesthetic and architectural criteria. Todeschini & Japha, for example, who carried out surveys for the Cape Town Municipality on the suburbs of Rondebosch and Mowbray (1990) and the Constantia Valley (1991) state in both reports that their criteria were architectural, and that “archaeology and history are outside the scope of the report”.

All this is not to suggest that there has not been any research into industrial sites. Sharma Saitowitz, an archaeologist at the University of Cape Town, recently published what may justly claim to be South Africa’s first industrial archaeology book. This detailed study looked at the short lived glass factory, built at Glencairn on the Cape Peninsula, in the early twentieth century.

The state heritage body in South Africa is the National Monuments Council, while the legislation protecting the historic environment is found in the National Monuments Act of 1969, amended in 1986. While the Act gives the National Monuments Council wide ranging powers to protect any building more than fifty years old, it simply does not have the resources to enforce them.

The Council employs a single archaeologist to cover the whole of South Africa, and one Maritime Archaeologist to take care of more than 2,000 shipwrecks. A large number of its staff have architectural backgrounds, and this is reflected in what we seen identified as National Monuments. Only 5% of the National Monuments in the Cape could be said to be of industrial nature.

Commercial developers’ seeking to re-use industrial sites, are generally under no obligation to assess or retain cultural significance when designing new schemes. Thus a number of potentially significant sites in Cape Town, such as the Rondebosch flour mills; the United Tobacco Company factory complex in Kloof Street; the Dock Road Power Station (recently opened as Planet Hollywood); the Salt River Power Station (demolished a few months ago); and the Salt River Railway Works, had no proper assessment of their cultural significance carried out before their archaeological value was either destroyed, or at best severely compromised. In each of these cases, architects and business economists dictate a scheme’s design. Cultural significance, call it “heritage” if you will, is simply not an issue, and is discarded no matter how embedded in the fabric it might be.

A recent dispute at Cape Town’s “Waterfront”, in the older part of the docks, has provided a sad example of legislative impotence. Despite official disapproval, original fixtures and fittings have been removed from a Victorian Power Station and replaced with the globally marketed images for which “Planet Hollywood” is famous (or infamous).

In a recent lecture in Cape Town, renowned environmentalist Richard Leakey spoke of the difficulties that even the best willed governments have in prioritising environmental conservation where there are competing and desperate needs for water, housing, health care and education. Sadly, the same must be true for the historic environment.

Case Studies

A selection of case studies illustrates the ways in which the industrial heritage is neglected.

Albion Spring , Rondebosch

Albion Spring is an early nineteenth century water mill site, which was later used to supplement Cape Town’s water supply and to provide water for Ohlsson’s Brewery. From 1926 until 1974, Schweppes operated a mineral water bottling plant on the site.

When the site came up for redevelopment, it contained the pump house and other buildings used by the City’s Waterworks; the Schweppes factory; and traces of the original Albion Mill.

The City Council assessed the “conservation worthiness” of the site in terms of an earlier conservation study based solely on aesthetic and architectural criteria, whilst archaeological contractors were briefed only to look for traces of the old mill. The 1920s mineral water factory didn’t earn a second look from anyone, and was subsequently demolished. Conservation policy, such as it was for the “pretty buildings”, deemed that they were saved for re-use, but without any statement of cultural significance being drawn up.

United Tobacco Company, Cape Town

The United Tobacco Company in Cape Town is acknowledged as “a particularly fine complex of early industrial buildings, the first in the Upper Table Valley”. The tobacco company operated out of the premises until the 1950s, and in recent years the site was used as a council depot. It has now been converted into film and television studios, with restaurants and other facilities.

Although all the principal buildings were retained, all discussion of the site and its future hinged solely on architectural concerns. One developer called it “an excellent example of turn of the century architecture”, describing it as “rationally planned, structurally advanced for the time, and very well detailed.” Yet at no time in the whole process did anyone ever carry out a study to inform a proper understanding of the site, or try to establish what was significant about the site, other than its architecture.

The Victoria and Alfred Waterfront and Cape Town Docks

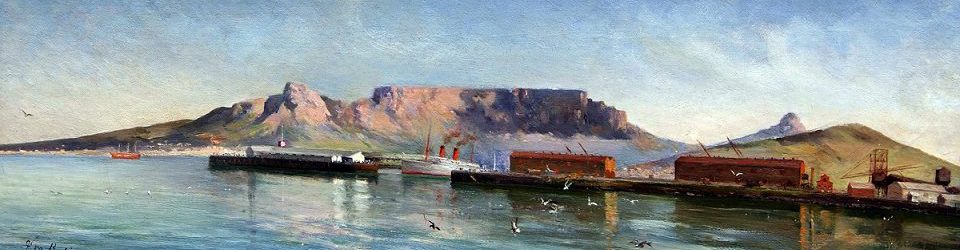

Although Cape Town’s first pier was built as early as 1656, the story of the existing harbour starts in 1860 with the building of a new breakwater. The Victoria and Alfred Waterfront, in the historic part of Cape Town’s harbour, has been developed for a mixture of retail, commercial and residential use, and has become a key focus of Cape Town’s tourism and entertainment industries. It is a complex development, involving dozens of historic structures, some of them National Monuments, as well as many new buildings.

A policy document by the City Council stated its intention to “Seek to preserve those precincts, buildings and structures which form an important part of the waterfront heritage”, and declared that the “area should remain a working harbour which combines compatible commercial, industrial and harbour activities with recreational and residential activities”.

Yet in spite of all that, the emphasis has again largely been on architectural issues, and there has been no attempt to understand the place in a broader context.

The Grain Elevator at Cape Town Harbour

The introduction of bulk grain handling was a result of government initiatives after the First World War to promote South Africa’s maize exports.

‘Country elevators’ were built at railway stations in South Africa’s maize producing areas, with port elevators being built at Cape Town and Durban. The functions of the system, included the grading, weighing, cleaning, storing and handling of grain.

The Cape Town elevator is built of cast ferro-concrete, and when it opened in 1924 was South Africa’s highest building, at 180 feet (57 metres). A contemporary newspaper reported that work continued on the “grey towering slab of concrete” throughout the day and night, with up to 1,000 men being employed on the construction at any time.

Grain is received in the track shed, where railway trucks are tipped by hydraulic lifts. It is then raised to the top of the working house by bucket elevators. Horizontal conveyors lead to a jetty, where two of the four original ship loaders still stand.

A storage annexe stands separated from the working house, connected by bridges to the scale floors of the working house, and tunnels to the basement of the working house. The larger, circular grain bins in the storage annexe, are each capable of containing approximately 500 tons of grain, while set in the spaces between the larger bins are thirty smaller ‘star’ bins.

Most of Cape Town’s Elevator complex has been leased by the port authorities to a farmer’s co-operative since 1987. The increased length and draught of modern bulk grain carriers means that many are now unable to berth at the Collier Jetty, and high railage costs from the maize producing areas, have resulted in the virtual cessation of grain exports from Cape Town. Although the last export shipment from the elevator was loaded in July 1995, today the elevator still serves a valuable warehousing and distribution function for Western Cape farmers.

The Grain Elevator complex is a unique industrial site, within the broader landscape of Table Bay Harbour. Its significance was originally in terms of international trade, and the facilities it afforded to the national and regional agricultural economies, though in more recent times, its importance has been of a regional nature.

It is also a significant factor in the “working harbour” which the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront Company originally claimed it wished to integrate with the modern development.

In 1995, I undertook a study on the elevator as part of a wider conservation study of the area. Its significance was assessed in terms of the broad criteria that one hopes to apply to industrial sites, but the study was undertaken in terms of a brief given by an architect. It did not go far enough, I would now suggest, in addressing the issues affecting the vulnerability of the site’s significance, or in proposing policies for the conservation of that significance. The site is now threatened with demolition, even though it is still basically performing the function for which it was built.

The Woodstock Gas Works

The first use of gas in Cape Town was in 1842, when the Presbyterian Church installed a small plant producing gas from whale oil.

Initial proposals for a Gas Works were described as “a ridiculous proposition” by the Cape Town Mail in 1843. It claimed that London was “becoming ashamed of gas”, and called it “an antiquated absurdity”.

However, in 1844 the Cape of Good Hope Gas Light Company laid the foundation stone for South Africa’s first public gas works. By 1862 the company supplied 253 street lamps, nearly all public and mercantile buildings, and a considerable number of private residences.

At about this time, there was also a small gas works in Table Bay Harbour, about which virtually nothing is known.

In 1888 a second gas company was formed to supply the newly evolving southern suburbs of Cape Town, and started to build its works on reclaimed ground in Woodstock. These potential rivals were merged in 1890 as the Cape Town and District Gas Light and Coke Company Ltd. It was to be 1895 before electricity eventually supplanted gas lighting in Cape Town’s streets.

A new retort house was built at Woodstock in 1907, and production was shut down at the now worn out Long Street site in the following year, though offices and showrooms were retained at the site..

In recent years a combination of economic factors meant that the gas works in Woodstock was no longer viable, and at the end of February 1996, it ceased production. At that time, it is believed that it was the sole surviving Victorian gas works still in commercial production anywhere in the world.

The most striking feature of the Woodstock gas works site was the retort house, actually two separate structures, built in 1907 and 1948. These structures contained a total of 46, refractory-lined, vertical retorts, and comprised little more than a steel frame with a brick fill, erected to protect the retorts from the elements. The retorts were heated by producer gas, which in turn was the product of burning coke in a reduced air supply, in producer fires at the base of each bed. Coke, coal tar and ash were all sold as by-products. Producer fires were gravity fed with coke from steel bogies, pushed by hand along a rail track, whilst coke discharge, or “slacking off”, took place at ground level.

The gas was passed through a set of Livesey washers, Ammonia washers, and through dry purification beds before being stored in spirally guided gas holders. From the gas holders, the gas was distributed to customers by means of either low pressure or high pressure mains.

The Woodstock Gas Works was a wonderful example of a dirty, smelly, unsightly, and uneconomic industry. As an industrial complex it had played an important part in the development of Cape Town’s industrial, commercial and social landscapes. Yet not only was it not possible to motivate any support for its conservation, there was not even sufficient support for adequate recording to be carried out, and it was demolished within months of closure.

In the case of the Woodstock gasworks, it was argued that the archiving of builder’s and engineer’s drawings rendered the proper recording of the site unnecessary before demolition. Such a view completely fails to address the archaeological issues, and needs to be constantly resisted. We know that it is not enough to assume that what was planned is what was built, or that it didn’t change over time.

Strategies for the Future

It is necessary to consider what strategies might be employed to ensure that the neglect our industrial heritage has suffered in the past, is not perpetuated in the future.

Robben Island is currently being nominated as a World Heritage Site, as indeed are Table Mountain, the Kruger Park, and a number of other sites in South Africa. Whatever else one may argue about World Heritage Site status, it unarguably confers recognition on a site in a way that the lay public can understand, and take a pride in.

It is now being suggested that the “Big Hole” Mine at Kimberley should be considered for World Heritage Listing. It is the largest man-made hole in the world, and by that I mean it was dug by men with picks and shovels, not machines, and it is central to the story of South Africa’s diamond mining industry. Designation as a World Heritage Site would undoubtedly start to foster a different attitude towards industrial sites.

The National Monuments Act is recognised as being well overdue for replacement. A Draft National Heritage Bill was approved at provincial level in July 1997, but has yet to go before the national parliament. The new legislation, if enacted, provides for local designation of “heritage sites”, and is likely to lead to a more balanced approach to the selection of monuments than has been the case until now. Grassroots involvement in the selection of sites of significance in the historic environment is also likely to lead to a greater public awareness of what it means to conserve that environment.

Research into industrial sites is beginning to be actively encouraged. Chemical giants African Explosives and Chemicals Industries, commissioned a Cultural Resource Management Report on their vast Somerset West dynamite factory site, before decommissioning it in 1996. What will become of the report’s recommendations, when cultural significance has to compete with the wholly justifiable economic demands of a profit driven organisation remain to be seen. The same company is now funding post-graduate research into what was once the world’s largest dynamite factory on it’s Modderfontein site.

In Cape Town, our own Research Unit currently has four post graduate students looking at issues around the industrialisation of the city, including my own research into Cape Town’s gas supply industry.

Much of what I have said here today refers to South Africa’s need to gain a proper understanding of its industrial heritage. One of the best hopes for the conservation of that industrial heritage lies in persuading all interested and affected parties of the most effective way of managing the conservation of the historic environment as a whole.

The Conservation Plan methodology, designed and employed extensively by Dr James Kerr, is as suitable for addressing the conservation of industrial sites as it is for any other place.

In its simplest terms, Kerr’s methodology may be described as a four stage process. It starts with the need for a proper understanding of the site. This is followed by clear statements outlining the absolute and relative significance of the site and its components, and an assessment of issues which may have an effect on that significance. In short, it asks, how is that significance vulnerable? Finally, policies are formulated for the retention of significance.

Because the Conservation Plan is based on a multi-disciplinary approach, it mitigates against over emphasis on any one discipline at the expense of others; while the clear distinction between assessment of significance and formulation of policy means that the assessor does not have to consider if or how a site can be re-used when working out whether it has cultural significance or not.

It seems likely, therefore, that the adoption of Conservation Policy methodology, rather than an adherence to the architecturally based “conservation studies” of the past, would be likely to see industrial sites examined in a more objective manner. This in turn would promote a greater understanding and appreciation of such sites, and make the retention of important sites more likely.

The challenge for South Africa’s industrial heritage, must be to raise public awareness and concern for sites under threat. This will only happen if the need for a proper understanding of sites is acknowledged before decisions are made that affect their future, and if the significance that is revealed by that understanding can be shown to be relevant to South Africa’s broad public, and not just to a minority of decision makers. In Britain, the industrial heritage is an undeniable aspect of national identity, encompassing notions of the Industrial Revolution and Empire. In a developing country such as South Africa, the colonised rather than the coloniser, people’s perceptions of industrial heritage are bound to be different. Britain takes pride in its industrial heritage. Is it reasonable to expect the average South African to feel the same?

We need therefore to start thinking in terms not just of cultural significance, but of ‘heritage values”, as discussed in the English Heritage document “Sustaining the Historic Environment”. This would allow us to acknowledge educational, economic and recreational values, alongside aesthetic and cultural values. Relevance must come through education, and it is therefore imperative that means are found of integrating the country’s industrial heritage into the outcomes based curriculum now being introduced.

Summary

We have seen how Industrial Archaeology in South Africa is largely a neglected discipline, and how this neglect impacts negatively on the conservation of the industrial heritage: firstly through a lack of understanding of such sites, and of any cultural significance attached to them, and secondly through the lack of properly defined conservation policies which might serve to retain that significance.

The case studies selected give a taste of what has already been lost, and suggest how important it is that adequate strategies are implemented for the future. The key to such a strategy is the formulation of proper conservation plans for industrial sites, rather than a continued dependency on aesthetics driven conservation studies; an educational model that integrates the historic environment into the curriculum; and acknowledgement of a broader range of heritage values than has been used until now.